Scooped!

It’s the writer’s biggest fear — while plugging away on a book, or querying that book to agents, or on submission to editors, perhaps languishing there for months or years, an announcement comes out in Publishers Weekly or Publishers Marketplace about a big deal for an eerily similar book. It’s hard to describe the sinking feeling, along with the pang of uncertainty: Is the book really as similar as the announcement makes it seem? And if the big-deal author is represented by an agent the poor writer queried, or published by an imprint to which the unpublished writer’s agent submitted the book a while ago to a rejection or, even worse, a no-response, the question tugs, over and over: Could some of my book’s DNA have ended up in the other book?

Being scooped is the scientist’s worst nightmare. Short of the lab blowing up, that is.

Welcome to The Scoop. Journalists are familiar with having the scoop — the coveted first story on a newsworthy event — as well as with having a story they’re pursuing scooped by a rival media outlet. Academic researchers deal with it all the time. If you’re a grad student in the hard sciences, pursuing grants to carry out multi-year research projects, you don’t want to find out — just as you’re writing your article, or it’s in the peer-review process — that another lab on the other side of the country or world has published the results of nearly identical research. Yes, you can find a less prestigious journal to publish your results — probably — but they’ll only confirm someone else’s “groundbreaking” discoveries. There aren’t many good solutions for the scientist who has been scooped. Perhaps the results are different enough that they challenge the other lab’s methodology, or there’s room to explore a research tangent. It helps, both to avoid being scooped and to recover from a partial scoop, to stay in communication with others in the field, to know what other labs are doing and make sure work that requires expensive and long-term investment complements rather than duplicates others.

Unfortunately, writers, especially writers of fiction, work alone and often in secrecy. We’re paranoid about our work in progress, lest someone run off with our high concept (or not so high concept) ideas. Yes, this can happen. But the secrecy has a downside if one avoids using beta readers or submitting manuscripts to agents and publishers. As I learned from experience, scooping doesn’t matter if your book never leaves your hard drive, because without outside readers it won’t become better and a book can’t be traditionally published unless it’s submitted to agents and editors.

Copyright law doesn’t protect ideas, only the expression of the idea. If someone lifts entire paragraphs of your unpublished or published work, you have a claim, as dozens of romance authors did when #cutpastecris plagiarized them to keep up her demanding schedule of self-published novels. Otherwise, though, ideas are vague and malleable. They float in the universe waiting for one or hundreds of writers to add their own voice, characters, and experiences. For the most part, the existence of one book doesn’t preclude another. How many recent novels for teens, for instance, contain a school shooting as a major plot point? Marieke Nijkamp’s 2016 novel This Is Where It Ends was a bestseller, but four years later, it hasn’t kept Liz Lawson’s The Lucky Ones from coming out to great attention and acclaim, along with at least a half dozen in between. In a country that has seen its share of mass murders in schools since the Columbine massacre 21 years ago, it’s, sadly, a topic on the minds of most young people.

Copyright law doesn’t protect ideas, only the expression of the idea. If someone lifts entire paragraphs of your unpublished or published work, you have a claim, as dozens of romance authors did when #cutpastecris plagiarized them to keep up her demanding schedule of self-published novels. Otherwise, though, ideas are vague and malleable. They float in the universe waiting for one or hundreds of writers to add their own voice, characters, and experiences. For the most part, the existence of one book doesn’t preclude another. How many recent novels for teens, for instance, contain a school shooting as a major plot point? Marieke Nijkamp’s 2016 novel This Is Where It Ends was a bestseller, but four years later, it hasn’t kept Liz Lawson’s The Lucky Ones from coming out to great attention and acclaim, along with at least a half dozen in between. In a country that has seen its share of mass murders in schools since the Columbine massacre 21 years ago, it’s, sadly, a topic on the minds of most young people.

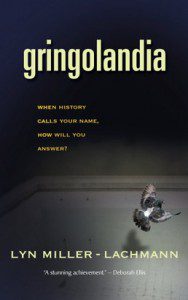

The danger of being scooped is greater with picture books with fewer words and a heavier reliance on the concept. It’s also the case with more obscure topics, where the question becomes how many of this kind of book the market will bear. As a budding historian in graduate school, I saw multiple scholars investigate the same archive, looking for different aspects or interpretation of individuals and events. Multiple scholars could explore, say, the Dirty Wars in the Southern Cone of South America in the 1970s and 1980s because they conducted their research without considering its commercial value, as scholarly journals and book publishers are generally subsidized by universities and part of the “publish or perish” ecosystem. But novelists must compete for existing readers or create new ones, and “we already have a book about…” is a common rejection line. Gringolandia was already in ARCs when Gloria Whelan’s The Disappeared came out in fall 2008, and although the books themselves are quite different, the Dirty Wars was, and probably still is, a “how much can the market bear?” topic. Had Gringolandia not come from a small press confident in its choice, I may have ended up with a cancelled book. And because I’m a history geek with a passion for obscure moments in history that parallel our present situation, the scoop lightning struck me twice.

The danger of being scooped is greater with picture books with fewer words and a heavier reliance on the concept. It’s also the case with more obscure topics, where the question becomes how many of this kind of book the market will bear. As a budding historian in graduate school, I saw multiple scholars investigate the same archive, looking for different aspects or interpretation of individuals and events. Multiple scholars could explore, say, the Dirty Wars in the Southern Cone of South America in the 1970s and 1980s because they conducted their research without considering its commercial value, as scholarly journals and book publishers are generally subsidized by universities and part of the “publish or perish” ecosystem. But novelists must compete for existing readers or create new ones, and “we already have a book about…” is a common rejection line. Gringolandia was already in ARCs when Gloria Whelan’s The Disappeared came out in fall 2008, and although the books themselves are quite different, the Dirty Wars was, and probably still is, a “how much can the market bear?” topic. Had Gringolandia not come from a small press confident in its choice, I may have ended up with a cancelled book. And because I’m a history geek with a passion for obscure moments in history that parallel our present situation, the scoop lightning struck me twice.

Like Gringolandia, my novel set in Portugal in 1966 under the Salazar dictatorship and its companion, set there one year later, portray life under a right-wing dictatorship and how teens survive while often challenging the constraints on their lives and their dreams for the future. My coverage of the 40th anniversary of the Carnation Revolution on this blog and elsewhere inspired the first book, titled THE HOUSE OF SILENCE, which I spent the next few years researching and writing before it went out on submission to publishers in April 2017. Over the next year and a half, it received two rejections — “too quiet” and “wasn’t the story I expected” — and a whole lot of silence. Then, in January 2019, the announcement came of a similar book set in fascist Spain under Francisco Franco in 1957 with the title The Fountains of Silence. The book, from acclaimed, bestselling author Ruta Sepetys — whose earlier novels Between Shades of Gray and Salt to the Sea are ones I greatly admire — was due out in October.

Like Gringolandia, my novel set in Portugal in 1966 under the Salazar dictatorship and its companion, set there one year later, portray life under a right-wing dictatorship and how teens survive while often challenging the constraints on their lives and their dreams for the future. My coverage of the 40th anniversary of the Carnation Revolution on this blog and elsewhere inspired the first book, titled THE HOUSE OF SILENCE, which I spent the next few years researching and writing before it went out on submission to publishers in April 2017. Over the next year and a half, it received two rejections — “too quiet” and “wasn’t the story I expected” — and a whole lot of silence. Then, in January 2019, the announcement came of a similar book set in fascist Spain under Francisco Franco in 1957 with the title The Fountains of Silence. The book, from acclaimed, bestselling author Ruta Sepetys — whose earlier novels Between Shades of Gray and Salt to the Sea are ones I greatly admire — was due out in October.

This happened at the same time that my agent retired. I immediately shelved THE HOUSE OF SILENCE and its verse novel companion, awaiting The Fountains of Silence to see how similar it was to my efforts, and concerned about how many books on this topic the market will bear. With the exception of Nazi Germany and the Holocaust, U.S. publishers have typically brought out more historical novels about freedom struggles in or dramatic escapes from Communist countries. Fortunately, I didn’t have to wait long. Usually books are announced 12-18 months before publication, but this one had been in the works, in secret, for many years and was ready for publication.

This happened at the same time that my agent retired. I immediately shelved THE HOUSE OF SILENCE and its verse novel companion, awaiting The Fountains of Silence to see how similar it was to my efforts, and concerned about how many books on this topic the market will bear. With the exception of Nazi Germany and the Holocaust, U.S. publishers have typically brought out more historical novels about freedom struggles in or dramatic escapes from Communist countries. Fortunately, I didn’t have to wait long. Usually books are announced 12-18 months before publication, but this one had been in the works, in secret, for many years and was ready for publication.

After reading The Fountains of Silence as soon as it came out in October, I feel like a tournament athlete bested by a master who goes on to win the entire thing. I read the novel as a writer looking for what I can learn from an acclaimed author, and I’ve started to make notes for how I can add action, agency, and additional layers to my Portugal manuscript, which I’ve now retitled. I think the books are different enough that I can revise mine and resubmit it, using hers as a comp, or comparative title. In the meantime, I’m grateful that The Fountains of Silence is out in the world, and its author has the skill and reputation to give it impact. At a time of rising right-wing authoritarianism all over the world, in many cases hand-in-glove with religious fanaticism, The Fountains of Silence is a reminder of what life is like under these oppressive regimes. I reviewed the book for The Pirate Tree last November and addressed one of those unfortunate echoes in the present:

Ruta Sepetys’s fourth YA novel…has emerged at a particularly fraught moment, one that has given this “hidden history” outsized significance. The history in question involves more than 300,000 infants and children taken from poor and/or politically suspect families and sold abroad or to supporters of Generalíssimo (Supreme General) Francisco Franco immediately after the fascists’ victory in the Spanish Civil War and in the three decades that followed. As far-right religious leaders such as Robert Jeffress threaten a second Civil War in the United States and thousands of undocumented migrant children have been separated from their parents at the border and are now unaccounted for, The Fountains of Silence has gone beyond a meticulously researched, atmospheric YA novel to a must-read by teens and adults alike as we search the past for insights into our experiences today.

I hope that this novel finds a wide audience and rather than cornering the market opens it to new perspectives and other accounts of life under fascist regimes. Even though they share the Iberian Peninsula and suffered under decades-long dictatorships, there are huge differences between Spain and Portugal during this period. For one — which had continued to have political and cultural impact — the Portuguese dictatorship was toppled in a military coup with democratic and socialist roots, while Spain’s dictatorship ended with Franco’s death and a negotiated transition to democracy that spared his underlings from prosecution for their crimes against humanity. And while the Spanish dictatorship came to power through war — the civil war that lasted from 1936 to 1939 and became a proxy for the Second World War — Portugal slid gradually into dictatorship from 1926 to 1929; however, Portugal’s dictatorship ended amid multiple colonial wars in Africa with similarities to the U.S.’s war in Vietnam.

Gringolandia survived a scooping and thrived — and so will my newer books.

Right now, I’m busy with other projects, but I’m not going to let the scoop stop me for long. I will revise the finished book and finish the one in progress. The more books out there, the better!

Have you ever experienced the scooping of your book? How did you respond? In my next post, I’ll discuss comps, and why it’s important to have them, even if you fear “comparative” may be “competitive.”

I think it’s fabulous that you’re writing fiction set in times of terrible repression–both Chile & Portugal. English-language readers are so ill schooled in those periods of recent history.

Years ago, when I submitted a book for young children to a new imprint at one of the big houses, I eventually heard back that they had recently acquired a book by a known author that was too similar to mine. I mean, mine was too similar to it. That was disappointing, but I hadn’t worked with an agent & had no reason to think my concept had been stolen.

I’m now a published picture-book author, & I do worry about being scooped! Even in my illustration style, which I kept mostly secret till the cover reveal. When the art style is a major feature of one’s debut author-illustrator book, there’s that nervousness . . . But it worked out great; the book is unique & reviewers have loved the art.

I’m working on a nonfiction PB now, & definitely on high alert about scooping possibilities!

Thank you for sharing your experiences, Ruth! Often when an imprint responds with a “too similar to something we already have” rejection, it’s only a no from that imprint. If the book they’re publishing does well, others may want to get in on the action and it’s a door opening rather than a door closing. Congratulations on Picturing God! It really is a unique and beautiful style of illustration.

Thank you very much, Lynn!

Oh Lyn. What a challenging experience. Yes, I have been scooped in regard to one of my middle grade novels. While querying it, someone else came out with a novel with similarities. I thought about shelving the book permanently after that. While querying a science fiction novel, someone else came out with a video game with a very similar premise. A friend brought the game to my attention. I wound up shelving that book permanently

I think we’re too quick to shelve on the basis of similarities, especially if it’s a book and some other medium. When I was in elementary school and beginning to read longer books, I gravitated toward novelizations of movies that I’d seen recently. (In those days, they were called “bovies.”) Video games also inspired the way I put together my novels, particularly the way game characters collect objects that seem extraneous but prove useful later on in the quest. And my most recent YA historical was inspired by a miniseries, which I learned a lot from but also felt frustrated because it featured a lot of characters and the teens responsible for the inciting incident and much of what happened later were not portrayed with much depth. I wrote my book because I wanted to know more about these idealistic kids who’d put themselves in so much danger.