Fighting the Last War

Last weekend I attended a panel of children’s authors at the Brooklyn Book Festival, all of whom talked about how they challenged themselves with each new book. (More to come on that topic next week.) Their comments made me think of a long-gone Twitter discussion in which children’s and YA authors commiserated about their negative professional reviews in 140 characters or less. One writer friend was dinged for “too many issues,” a problem so common to diverse authors that Malinda Lo wrote a much-circulated blog post calling out that criticism.

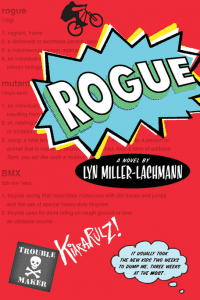

I, too, suffered from the “too many issues” criticism for Rogue. Even within my publishing house, people objected to the main character being both autistic and biracial/bicultural, the parents split apart for economic reasons, and the abused neighbor boys whose parents operate a meth house. In previous drafts of Rogue I had taken out additional issues — a family friend’s alcoholism and the death of a major secondary character — so I was already aware of my tendency to lose focus. And whether or not actual readers were troubled by the number of issues (because many middle grade and young adult novels have tons of issues that sometimes seem thrown in but other times are woven in so well that they add real complexity and depth to the story), I felt stung.

I, too, suffered from the “too many issues” criticism for Rogue. Even within my publishing house, people objected to the main character being both autistic and biracial/bicultural, the parents split apart for economic reasons, and the abused neighbor boys whose parents operate a meth house. In previous drafts of Rogue I had taken out additional issues — a family friend’s alcoholism and the death of a major secondary character — so I was already aware of my tendency to lose focus. And whether or not actual readers were troubled by the number of issues (because many middle grade and young adult novels have tons of issues that sometimes seem thrown in but other times are woven in so well that they add real complexity and depth to the story), I felt stung.

As a result, in my next project I decided to address the “too many issues” problem head-on, by taking out all but the one big theme of the book. And so I had an all-white cast, removing even brief references to the (realistically for the region) part Native American heritage of a secondary character. The romantic relationship ended without violence or an unintended pregnancy. Every scene had some relation to the overarching theme of class and inequality, as the working-class protagonist, having lost his slot in an elite academic program after an assault that he instigated by publicly humiliating his well-to-do rivals, struggled between trying to get back what he’d had or give up his ambitions and take his place within the community that accepted him and kept him safe.

After two years and four drafts, I was forced to acknowledge that this new book — the first one I wrote after Rogue — had failed. When my agent sent it out at the end of 2013, 11 of 12 editors who received it never responded. The other was a rejection; while she had nice things to say about my writing, she couldn’t connect with my protagonist in the first two chapters and read no further. I revised once and sent it back to my agent, who at this point said it was “too on the nose.” A beta reader who had graduated from VCFA several years before me said the story “needed layers.”

For the already published author, writing a failed manuscript is both a source of shame and a very real threat to stalling a career. This is especially true if one spends two years on the project, drafting and revising, as I did. In recent years, though, there has been a growing body of work on the value of failure, and reading those books and articles, I rediscovered my lost confidence and started a brand new project — and one after that. One learns from failure, and I learned several things from this humbling experience.

The first is the danger of “fighting the last war.” Just as generals overreact to a lost battle by following the opposite strategy in the next one, I overreacted to the negative feedback on Rogue, stripping out all the issues that drew readers to the book and kept them turning the pages. People want a story, not a lecture. They want a protagonist with a full, rich life — one that mirrors real life in all its complexity and messiness. Like the failed manuscript, Rogue is set in a working-class community, and while all the other stuff is going on, readers subliminally understand the difference between Willingham and College Park. The novel has what the beta reader called “layers.”

The second is letting failure define me as a writer. After Gringolandia‘s glowing reception, the harsh judgement of Rogue stunned and rattled me. I saw myself as a failure despite the loyal support of the book’s middle school age readers and the adults in their lives. So I created a protagonist who was also a failure. After the assault, he flunked out of the elite program and went into a tailspin that jeopardized his relationships with his parents, his disabled stepbrother, his new girlfriend, and the teachers who’d believed in him. He was true to me and my experience, but no one wants to read about a failure. His redemption came too late in the story. My challenge in my next project was to get beyond the experience of failure and exclusion, the “chip on the shoulder” (which I liked in my protagonist but apparently no one else did) to create a more likable and sympathetic character. And with this new book, it has taken me now four drafts and the support of a whole lot of writer friends to excise that stench completely.

The third is letting go. In the months before the 2016 election, this book about a white working-class teenager stripped of his only asset — his academic ability — in large part due to his own bad decisions, became suddenly relevant. I decided to rewrite changing the point of view from a distancing third-person present tense to a more sympathetic first-person past tense. In doing so, I set back my next project six months and didn’t make this book appreciably better for all the time I put into it. Writers can spend a lot of time reworking and reworking a piece that isn’t going anywhere, and may never go anywhere, when they should be starting something new. Every new project has something to teach and is an opportunity to grow. An old project may simply be a rut.

The fourth is appreciating the failed project for what it taught me. I changed the point of view and/or tense three times. I know a lot more now about point of view, first-person, third-person, present tense, and past tense, what they bring to the story and what they take away. I learned about character development and the need for complexity even if someone may call it “too many issues.” It all depends on how these issues are woven into the story. And I learned about the need for uplift, for kindness, for generosity of spirit. Yes, stories depend on conflict to build suspense, and yes, protagonists need to be imperfect to grow. But the reader has to connect with a character right away and difficult circumstances alone aren’t enough. Right away, there has to be a spark of generosity, of caring about others, of optimism that things will get better and the journey is worth the struggle.

Lyn –

Thank you for writing this honest and heartfelt post. I especially liked reading your “lessons learned” — don’t fight the last war, don’t let failure define you, let go, and appreciate what you’ve gotten from the process. So far, I have only one novel out in the world, and writing the second one has been a struggle. While feedback on my first novel has been good overall, some students have told me they didn’t like my ending, and I’ve had trouble shaking that comment off. At times while working on my next novel, I’ve realized that I’m trying to please students rather than staying focused on my new set of characters and where their story needs to go. Oh, and the challenge of making a difficult character sympathetic—tell me about it! It’s so hard. I’m drawn to try to understand people whose views stand in opposition to mine. What value do they find in holding onto judgments and prejudices? What motivates them to cling to hate-filled ideas? These questions fascinate me. But when I showed my agent a rough draft of my current work in progress, she said she couldn’t imagine any reader wanting to spend 300 pages with this jerk of a protagonist. Hmmm. Okay, yes, she’s right. The challenge becomes: how to make this jerk sympathetic? People with antagonistic personalities also have redeeming qualities. I’ve had to dig deeper into this character—either that or scrap him and his story and begin a new project. But so far, I’ve held on. Something in the life of this difficult character speaks to me. I want to tell his story. I’m determined to keep plugging away, even if it takes me another few years. We often hear of novelists who say this or that book took them ten years (or more) to write. I get it now. Some take longer than others. I’m in it for the long haul. And I know you are, too. Hang in there.

Thank you for sharing your experiences, Anne! I’m sorry the students didn’t like your ending — I thought it was a great ending, entirely appropriate for the character and the time in which he lived. In unfree societies, people don’t have a lot of choices, and all the ones they have are bad in some way. As far as your new book, have you thought about it as an adult novel? I do find that in adult literary novels, there’s much more tolerance of unsympathetic protagonists, or ones that undergo a difficult (and mostly internal) learning experience. I’ve considered sending my unpublished novel to the university press that ended up with Gringolandia after Curbstone Press closed, and I may still do it because the book is allegorical — another no-no in YA.

Good question, Lyn. No, I haven’t thought about it as an adult novel, but I think you’re right that adults are more tolerant of unsympathetic protagonists. Interesting that you say allegorical is another no-no in YA. Sheesh! I hate all the supposed rules about what sells and what doesn’t. I hate thinking about markets at all.

I think one of the problems with YA as opposed to adult is the lack of a thriving small press ecosystem. (It’s also a challenge for increasing the number and range of books translated into English from other languages.) The adult small presses and university presses are good at selling to niche markets, but teens who don’t share mainstream tastes don’t have the same options and for the most part end up reading adult fiction earlier for that reason. Reviewers, teachers, and librarians are only beginning to understand the importance of giving small press titles fair consideration and support, but bookstores will not carry them, so it’s really hard for those presses to survive if they’re publishing YA. In fact, YA seems to be the toughest; there’s a real herd mentality attached to the media and fashion industries. I see the solution is two-pronged: push gatekeepers to become more open to small presses and encourage adult small presses and university presses to move into YA.

I’ve thought very little about the industry, itself, so reading this gives me a new perspective. Much to think about. Thank you!

Wow. Wonderful, thoughtful, deep post. Thank you, Lyn

Thank you for reading, Dean! I’m glad that it’s created a forum for thought and discussion.