Where to Invade Next and What to Translate Next

I saw Michael Moore’s film Where to Invade Next the week of its release in the United States, and I’ve noticed that it’s playing pretty widely in Europe too. I’m not surprised; the film features Moore traveling to various European countries to find things that they’re doing right. In Italy, he finds parent-child bonds strengthened by generous family leave. In southern France, he eats healthy school lunches in a quiet, orderly lunchroom. In Slovenia, he meets students whose university education is free. In Germany, in what is perhaps the most powerful segment of the film, he finds people of all ages confronting and acknowledging past atrocities rather than ignoring them or making excuses. In Portugal, he learns of the positive impact of decriminalizing drugs. In Norway, he travels to humane prisons that focus on rehabilitation, and in Iceland, he hears of the history of the women’s rights struggle and the difference a woman leader can make.

I’ve observed personally the emphasis on facing history as a nationwide project in Germany post-1989 (this post is an example) and the positive effects of decriminalizing drugs in Portugal. I wasn’t aware of the drug situation in Portugal before 2001, when all drugs from marijuana to heroin were decriminalized, but today the death rate from drug overdoses in Portugal is 3 per million, the second lowest in the EU. The rate in the U.S., by contrast is 135 per million. Drug-related crimes are almost nonexistent, in large part because the trade isn’t controlled by large gangs vying for turf and fighting the police.

I’ve observed personally the emphasis on facing history as a nationwide project in Germany post-1989 (this post is an example) and the positive effects of decriminalizing drugs in Portugal. I wasn’t aware of the drug situation in Portugal before 2001, when all drugs from marijuana to heroin were decriminalized, but today the death rate from drug overdoses in Portugal is 3 per million, the second lowest in the EU. The rate in the U.S., by contrast is 135 per million. Drug-related crimes are almost nonexistent, in large part because the trade isn’t controlled by large gangs vying for turf and fighting the police.

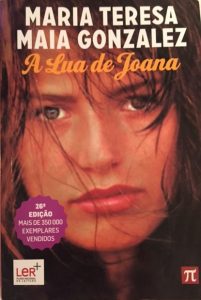

Last year I bought a young adult novel originally published in Portugal in 1994, Maria Teresa Maia Gonzalez’s A Lua de Joana (Joana’s Moon), which at 350,000 copies sold in 26 editions is one of the bestselling books for teens by a Portuguese author. The novel consists of Joana Brito’s letters to her best friend Marta over a period of two years, from when she is almost 14 to when she is about to turn 16. In the beginning, Joana is mourning Marta’s death from a drug overdose. A top student and student government representative from her class, Joana doesn’t understand how Marta chose drugs over her friends and everything else in her life. She cannot forgive Marta, but she also wonders if she could have done more to help. Was she a good enough friend? Writing a play with her classmate João Pedro, which draws in even more students as actors and stagehands, forces her to confront these questions. And while things are going well at school, Joana’s home life is less pleasant, especially after her parents become obsessed with her lazy brother and ignore her and her beloved grandmother — the only person who really “gets” her — falls gravely ill. In many ways, Avó (Grandmother) Ju’s death is the turning point of the story, because after she’s gone, nine months after Marta’s death, Joana feels as though she’s all alone in the world.

When Richard and I visited our friends Lígia and Jorge in Porto, I mentioned that I was considering translating A Lua de Joana, but the book lacks the “Hollywood ending” that appeals to U.S. teens and publishers. Lígia, who was the age of the book’s protagonist in the late 1990s, said, “But I loved the book…I cried at the end!” (I have to admit that I cried at the end too, as well as at several other times in the course of the story.) She went on to say that pretty much every teenager read the book in school, and it was quite popular, provoking discussions on the dangers of drugs, the meaning of friendship, and the important role that friends and family play in the life of a young person.

When Richard and I visited our friends Lígia and Jorge in Porto, I mentioned that I was considering translating A Lua de Joana, but the book lacks the “Hollywood ending” that appeals to U.S. teens and publishers. Lígia, who was the age of the book’s protagonist in the late 1990s, said, “But I loved the book…I cried at the end!” (I have to admit that I cried at the end too, as well as at several other times in the course of the story.) She went on to say that pretty much every teenager read the book in school, and it was quite popular, provoking discussions on the dangers of drugs, the meaning of friendship, and the important role that friends and family play in the life of a young person.

Widely read at the time as well as decades later, A Lua de Joana, according to Lígia, played an important role in changing attitudes toward the nation’s drug policy. Criminalizing drugs wasn’t working — more and more young people like the book’s characters were dying of overdoses, AIDS, and other drug related problems, including suicide, as well as of violence related to the drug trade. The 2001 law to decriminalize emphasized four strategies in its place — education, prevention, harm reduction, and treatment. While drug deaths are way down, the novel, with its sympathetic protagonist and multi-layered storyline, still plays an important role in educating young people not only about the dangers of drugs and how even “good” kids can be drawn in but also what it means to be a friend or part of a family. In my opinion, the best books are the ones that get readers to think; they’re the ones that stay with you and are remembered years later.

As literature in translation gains more and more attention, among the books that publishers should consider are those that have had a great impact in their countries of origin. In its emotional connection with hundreds of thousands of readers in a small country, and in its role in bringing about a drug policy worthy of adopting in the U.S., A Lua de Joana is one of those books.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks