What Are Comps and Why Are They Important?

When querying agents or submitting to publishers, writers often encounter the question, “What are the comps?”

“Comps?”

The word refers to comparative — or competitive — titles. Nonfiction book proposals (as most nonfiction is sold on proposal rather than with a finished book) require extensive lists of comps. My nonfiction proposals included an annotated bibliography of at least a half dozen similar titles, with a paragraph at the end of each annotation explaining how my book would be different from theirs — complementing rather than duplicating. Nowadays, with a much more competitive market for fiction and genres rising in popularity until they reach the saturation point, more and more agents and editors require a list of comps for both finished books and proposals. (Finished books vs. proposals in fiction: I’m saving that one for a future post.) There are several reasons why writers should include comps in their queries, but not all comps are equally effective.

The first reason to include comps is that fiction editors, like their nonfiction counterparts, want something that’s “the same but different.” As I’ve learned from unhappy experience, too much originality is not a good thing. If something on a given topic hasn’t been published before, it’s probably not because no one’s thought about it but because publishers don’t see a market for it. It’s weird. Niche. That’s what small presses do best, but nowadays they struggle in a publishing environment where too-weird writers can reach their targeted readers and make more money by going it alone. So if you have that weird book and want to publish traditionally, you need to find another roughly similar book or two that has garnered critical notice and sales to prove your project’s viability. At the same time, you need to show that yours is not too similar to the comps that it would be considered derivative, a mere knockoff of a successful author or franchise.

Missing my bus while reading…

The second reason is that listing comps shows a degree of professionalism. It means you are familiar with your category, genre, and subgenre where your project fits in. Many times a writer will query an agent with the statement, “This novel is a first,” or “There’s nothing like my manuscript out there,” and the statement is patently false. There are dozens of similar books out there! The topic may even be overdone, but writers who haven’t read widely in the area in which they write don’t know that. I’ve seen requests for lists of comps from people about to query a finished project, and the first thing I think is, “You wrote a book in a genre but you haven’t read anything else in the genre?” It means they don’t know the literature, the conventions of the genre — and some, like romance, have very strict conventions — tropes to avoid, or where their book fits in. It may signal they’re writing in a genre that they don’t respect enough to read anything else in or to support their colleagues but have seen #MSWL calls from agents or editors and are looking for a quick sale. Maybe I swing too far in the other direction, due to the fact that I come from a scholarly background where one needs an extensive knowledge of the literature to be taken seriously, but as writers, we engage in dialogue with other writers and with readers as part of a community. Not reading or even knowing about colleagues’ works means not choosing to be part of that community but setting oneself above it. It’s definitely not a good attitude to have when you’re starting out.

Writers are part of a community, in dialogue with others.

Yet it’s a common fear: “If I read too much, I’ll discover books that are too much like mine, and I’ll have to shelve a project I’ve worked on for years.” But while familiarity with the existing and forthcoming literature may lead to finding out you’ve been scooped, it can also help you avoid being scooped because you’ll rethink your scope and details before you start writing, or you can adjust in the middle of the draft, or at the revision stage as I’ll soon be doing. After all, as I wrote in my last post, scientists’ experiences with the same problem show

…it helps, both to avoid being scooped and to recover from a partial scoop, to stay in communication with others in the field, to know what other labs are doing and make sure work that requires expensive and long-term investment complements rather than duplicates others.

In other words, what you don’t know about comps is a bigger problem than what you do know.

Now that you’re familiar with what’s out there in your subject area, how do you choose comps for your queries and submissions? The general advice is not to list blockbusters — highly commercial franchises sitting at the top of bestseller lists year after year. The reason is this: Everyone cites the Harry Potters, and if that’s the limit of your familiarity with the genre, you haven’t read enough. The blockbuster may be too far a stretch for your book, put there to entice an agent but not enough to tell the agent what your book is really about, or its style. At the same time, a too-obscure comp may convey the hard-to-market niche nature of your project unless you can show with a second comp how your book may have wider appeal that the one that you loved but maybe you were the only one in the world who loved it. (I know that feeling!) Because trends and styles change, at least one of your comps should be recent, published in the last three years or so.

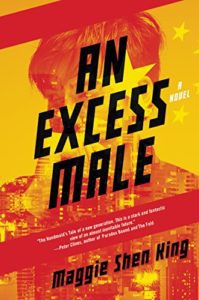

If you read widely, you can also find an unusual comp, one that doesn’t match the genre of your work but matches the distinct point of view or voice. For instance, my agent comped one of my books to Maggie Shen King’s An Excess Male. While it’s adult rather than YA, and near-future dystopian rather than mid-20th century historical, the two share multiple POVs that become a collective protagonist and an unusual family confronting an oppressive regime. In addition, Agent Jacqui compared the subject matter and style of my book to those of two acclaimed (and by me much admired) authors of YA historical fiction from that time period, Ruta Sepetys and Elizabeth Wein, without mentioning specific books. In contrast to a nonfiction proposal, a query letter for fiction doesn’t have to go into detail about each book and how yours is different. Thanks to my academic background, I produced an annotated list of more than a dozen recently published YA historical novels set in roughly the same time and place as mine. The agents I queried a year ago seemed to have ignored that list.

If you read widely, you can also find an unusual comp, one that doesn’t match the genre of your work but matches the distinct point of view or voice. For instance, my agent comped one of my books to Maggie Shen King’s An Excess Male. While it’s adult rather than YA, and near-future dystopian rather than mid-20th century historical, the two share multiple POVs that become a collective protagonist and an unusual family confronting an oppressive regime. In addition, Agent Jacqui compared the subject matter and style of my book to those of two acclaimed (and by me much admired) authors of YA historical fiction from that time period, Ruta Sepetys and Elizabeth Wein, without mentioning specific books. In contrast to a nonfiction proposal, a query letter for fiction doesn’t have to go into detail about each book and how yours is different. Thanks to my academic background, I produced an annotated list of more than a dozen recently published YA historical novels set in roughly the same time and place as mine. The agents I queried a year ago seemed to have ignored that list.

I’ve advised nine-year-olds and 60-year-olds and everyone else who wants to write that they should read widely, not only the classics but also recent books and those in similar age categories and genres to their own projects. Knowing your comps can help you at every stage of the process, from outlining the first draft to submitting the finished manuscript to agents and publishers. These mentor texts help you become a better writer, and by reading them, you become part of the larger literary community — all rewards no matter where your own book lands.

A great post! Thanks so much, Lyn!

Thank you, Sandra! I hope it helps people as they start to query their projects.

I agree with Sandra. Great post!

I wound up cutting some comps in a recent query I made, because I the authors who really inspired the comparison are no longer writing YA books. And I couldn’t think of any recent books that were a good comparison. I’ve heard too many negative comments from agents who didn’t like or disagreed with other comparisons (like when authors claim their book is like Harry Potter).

I wouldn’t leave out a title from your comp list because the author isn’t writing in the category or genre anymore. The book is still there! It may mean you don’t ask the author to blurb your book down the road because that author is out of the field. I have seen writers pair a book comp with a recent movie, and with the Hollywood-ization of YA, I think it’s an effective strategy.