Rural Lives, Rural Voices

After the recent election, many commentators have focused on divisions between urban and rural voters and the far higher proportion of rural voters who chose right-wing authoritarian leadership. For many, this feeds into a stereotype of rural residents as reactionaries seeking to preserve a mythical white-ruled utopia based on a Christian prosperity gospel, individualism, and free-market economics, one in which a majority living in poverty vote against their economic self-interest to preserve white supremacy. As described by Arlie Russell Hochschild and others after the 2016 elections, rural residents and their advocates tell a different story, one in which decades of being looked down on and passed by have led to choosing leaders who will defend them and control and punish their adversaries.

In fact, life in rural areas of the United States defies easy categorization in both past and present. In 1861, the western part of Virginia seceded to remain in the Union. West Virginia’s subsistence farmers and laborers, no fans of slavery, formed the backbone of the labor movement in subsequent decades. Mineworkers’ unions in Appalachia were among the most militant in pressing for shorter work days and weeks, better safety standards, and an end to child labor. More recently, activists throughout the South have successfully pushed for the removal of the Confederate stars-and-bars on state grounds and in their state flags. After South Carolina did so in 2015, I spoke to my friend and now agent-sibling Monica Roe about her work to dispel stereotypes, which also involves changing hearts and minds within the region.

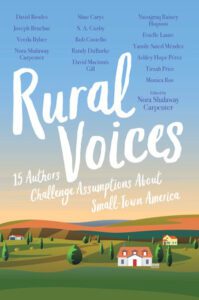

Five years later, Monica’s short story set in South Carolina, “The (Unhealthy) Breakfast Club,” is the lead story in an outstanding and important collection edited by my VCFA classmate Nora Shalaway Carpenter. Rural Voices: 15 Authors Challenge Assumptions About Small Town America features short stories, poetry, and essays for teens set in Alaska, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Michigan, New Mexico, New York, South Carolina, Texas, Utah, Virginia, and West Virginia. The first of these assumptions to be challenged is that rural residents are uniformly white. Among the protagonists are Black, Latinx, Asian, and Native American teens. The assumptions and stereotypes they confront are more about class than race. In S.A. Cosby’s “Whiskey and Champagne,” the wealthy boss who accuses the protagonist’s father of theft is also Black. White protagonists “counted out” because of their circumstances assert themselves in “The (Unhealthy) Breakfast Club” and David MacInnis Gill’s “Praise the Lord and Pass the Little Debbies.” Other stories, such as Veeda Bybee’s “Fish and Fences” and Yamile Saied Méndez’s “Island Rodeo Queen,” show solidarity and generosity across racial, ethnic, and class lines. We see also the dilemmas that queer teenagers face in small towns. For the protagonist and his boyfriend in Rob Costello’s “The Hole of Dark Kill Hollow,” it involves choices — to risk magic not to be gay, or to risk leaving their upstate New York town to be who they are. In Tirzah Price’s “Best in Show,” a series of mishaps on a girl’s first date with her crush leads to the possibility of coming out at the state fair, which has been the high point of her year ever since she was young. Life in small towns and on farms has no shortage of excitement and surprises, as the protagonist of Nora’s story “Close Enough” finds when a bull chases her and her friend up a tree.

Five years later, Monica’s short story set in South Carolina, “The (Unhealthy) Breakfast Club,” is the lead story in an outstanding and important collection edited by my VCFA classmate Nora Shalaway Carpenter. Rural Voices: 15 Authors Challenge Assumptions About Small Town America features short stories, poetry, and essays for teens set in Alaska, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Michigan, New Mexico, New York, South Carolina, Texas, Utah, Virginia, and West Virginia. The first of these assumptions to be challenged is that rural residents are uniformly white. Among the protagonists are Black, Latinx, Asian, and Native American teens. The assumptions and stereotypes they confront are more about class than race. In S.A. Cosby’s “Whiskey and Champagne,” the wealthy boss who accuses the protagonist’s father of theft is also Black. White protagonists “counted out” because of their circumstances assert themselves in “The (Unhealthy) Breakfast Club” and David MacInnis Gill’s “Praise the Lord and Pass the Little Debbies.” Other stories, such as Veeda Bybee’s “Fish and Fences” and Yamile Saied Méndez’s “Island Rodeo Queen,” show solidarity and generosity across racial, ethnic, and class lines. We see also the dilemmas that queer teenagers face in small towns. For the protagonist and his boyfriend in Rob Costello’s “The Hole of Dark Kill Hollow,” it involves choices — to risk magic not to be gay, or to risk leaving their upstate New York town to be who they are. In Tirzah Price’s “Best in Show,” a series of mishaps on a girl’s first date with her crush leads to the possibility of coming out at the state fair, which has been the high point of her year ever since she was young. Life in small towns and on farms has no shortage of excitement and surprises, as the protagonist of Nora’s story “Close Enough” finds when a bull chases her and her friend up a tree.

The A Júlia restaurant in the village of Ciborro, Portugal.

Because I have friends who live in rural areas of Portugal, and my forthcoming novel TORCH is set in a smallish town in a mining region of then-Czechoslovakia, now the Czech Republic, I read this book with an eye to comparing rural experiences around the world and across time. Like Rob’s protagonist, my character Stepan in TORCH sees his future in Prague with its underground gay clubs and relatively greater freedoms for someone like him. (He also comes to realize that freedom is ephemeral and something for which he’ll constantly have to fight no matter where he is.) Though less pronounced that in the United States, class distinctions existed in this Communist country, with some people having greater access to scarce resources and some lives considered more worthy than others. Even so, living on the scruffy edge of town, as Lida and her father do, confers the advantage of being able to trap rabbits and gather berries to supplement their ration coupons. Like many of the protagonists of the short stories, my teenage characters except for Stepan don’t dream of moving somewhere else; even if they attend university, they plan to return to contribute their skills and knowledge to their community.

And speaking of rural life, my husband and I finished watching A French Village, set in and around a small town in the Jura region of eastern France during and in the immediate aftermath of the WWII Nazi occupation. I think about that moment in the first season when a distraught mother brings her malnourished child to the village doctor and he asks her, “Do you have family living on a farm?” because that was the only way poorer residents of the town could survive the Nazi-imposed scarcities. Seeing that series has given me yet another perspective on Rural Voices.

And speaking of rural life, my husband and I finished watching A French Village, set in and around a small town in the Jura region of eastern France during and in the immediate aftermath of the WWII Nazi occupation. I think about that moment in the first season when a distraught mother brings her malnourished child to the village doctor and he asks her, “Do you have family living on a farm?” because that was the only way poorer residents of the town could survive the Nazi-imposed scarcities. Seeing that series has given me yet another perspective on Rural Voices.

Nora’s collection is an important step toward a more nuanced understanding of rural life among those who live in cities and suburbs, but it’s also for readers young and old who live in rural areas to see themselves in all their diversity. Everyone has stereotypes and assumptions that need to be challenged, including the prep-school classmates of the three Unhealthy Breakfast Club members, the small-town Black entrepreneur ignoring his own son’s problems, and the church leaders too wedded to the Prosperity Gospel to see the dignity and intelligence of those who question a doctrine that denies them God’s grace. Story by story, reader by reader, I hope Rural Voices can help undo the polarization that threatens the foundations of our democracy.