Not the Minor Leagues

Many years ago when my first adult novel, Dirt Cheap, came out, I took part in an authors’ panel at a conference in Connecticut. The other panelists were a debut novelist with a major house and an author of a memoir published by University of Wisconsin Press. The memoir author shocked the rest of us when she described her efforts to sell her memoir to a big publisher and failing that, “settled” for the university press. She said, “Small presses are the minor leagues,” hoping that this book would be her stepping-stone into the “major leagues” of the then-Big Six publishers.

I felt that I had to defend my choice of going with a small press for Dirt Cheap, an exclusive submission to Curbstone Press after editorial director Alexander “Sandy” Taylor and one of the press’s other authors, Marnie Mueller, mentored me through multiple rounds of revision. Gringolandia, my option book after Dirt Cheap, turned out to be “the little book that could,” winning multiple distinctions and awards despite its small-press provenance. At the same time, I had to push back against the “minor leagues” attitude of many of my colleagues. Because my publisher was too small and specialized in adult literary fiction rather than YA, I was excluded from every 2009 kidlit debut group, thereby losing opportunities for group marketing initiatives, key information about the industry, and a cohort of colleagues whose support and friendship I could count on as my career developed.

This “minor leagues” attitude extends to reviewers and gatekeepers. This month, trade journals and newspapers publish their “best of” lists, and books from Big Five publishers dominate. With books for children and teens — where these lists make a difference because kids typically don’t buy their own books but get them from parents, librarians, and teachers — very few small press books appear. Despite uniformly good reviews, Gringolandia didn’t make any of the end-of-year lists, though one month later it was chosen for the ALA/YALSA Best Books for Young Adults list. Starred reviews from these trade journals — and busy librarians often look for those stars and skip the rest — tend to elude small press books. Even when the review itself is glowing, the star seems to slip away. In the past two decades, I’ve written, edited, or translated eleven books, nine published by small presses and two by the same imprint of Penguin Random House. Two of those books have received one starred review each, one from PRH and one from the small publisher Enchanted Lion Books, which specializes in translated picture books.

With PRH’s acquisition of Simon & Schuster, announced today, the “minor leagues” stigma of small presses needs to die. The Big Five is now the Big Four, with more uniformity and focus on blockbuster titles. Do we really want all those “best of” lists to come from one publisher? The expected result of concentration at the top is fewer imprints, fewer books, and lower advances due to less competition for manuscripts and fewer bidding wars. Observers of the industry have pointed out that megapublishers typically chase trends; they aren’t a source of innovation, of trying new things and reaching audiences beyond the lowest common denominator. More and more, this responsibility for innovation will fall to small presses, as it already has for international literature in translation.

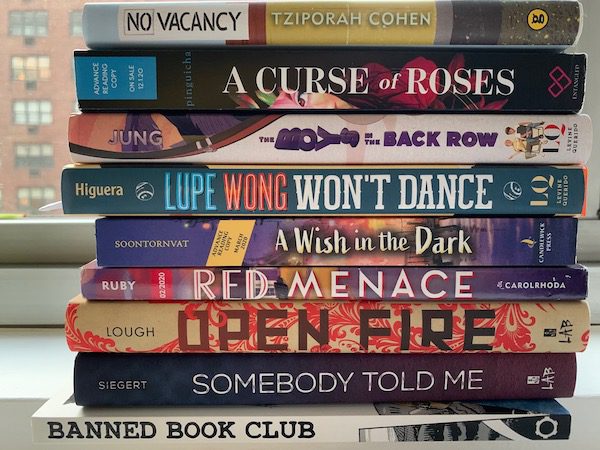

Some awesome MG & YA titles that came out from small presses in this most difficult year for new books.

I’d like to call on my writer colleagues, especially those fortunate enough to have been well-published by major houses over long periods of time, to give up the idea that small presses are the minor leagues and the books we write are less worthy of their support and attention. Attitudes that one is somehow better than someone else by virtue of outward measures of prestige and money are a problem anyway in artistic fields where quality beyond a certain point is subjective and much of one’s success depends timing, luck, and connections. An endorsement by a highly successful author can do a lot for a book that deserves attention but may not get it otherwise because the publisher is small and can’t market as extensively.

In addition, I call on reviewers to rethink how they give stars to books, or maybe not give them at all. When I edited MultiCultural Review, my boss suggested we give stars to outstanding books, and I argued that it would reduce the ability of our readers to select books based on the needs of their libraries. She ended up agreeing with me. Since then, I’ve reviewed for other publications, and I have no idea how their stars are given, but it seems to be the big books from the big publishers that get them. Does that mean they’re the “best” books? Does it mean an author who never gets stars is an inferior author? Does it mean the small press books that rarely receive stars are the minor leagues? As publishers consolidate and become less open to innovation and change, is this the message critics and gatekeepers want to send?

Now more than ever, it’s time to support our small presses! Do you have a favorite small press, a go-to for your favorite books? Share it with us to let others know about its goodness.

Well said, Lyn! Smaller presses are deserving of more recognition. Many years ago, I small press bought a manuscript I coauthored. It was later bought by a bigger publisher, which also was acquired by another.

I’d love to hear some small press suggestions.