Stories Dictators Tell

The post I’d scheduled to write last week — a piece of advice for writers — is fading into oblivion along with my colleague’s Twitter post that prompted it. Instead, I took out my copy of Arlie Russell Hochschild’s Strangers in Their Own Land that I bought at the Finalists’ reading for last November’s National Book Awards. The book follows a group of white residents of southern Louisiana who had joined the Tea Party even though the core of Tea Party beliefs — ending environmental regulations, redistributing wealth from the poor and middle class to the wealthiest 1%, and weakening the safety net for people who had experienced bad luck or made a bad choice (like getting pregnant in high school) — only made their lives harder. Hochschild writes about the “deep story” that has become the core of their lives and culture, the story that fuels their emotions as effective stories do and in turn drives their political behavior. And here is the dominant story, the one she heard over and over from these Tea Party members in Louisiana who would soon vote in lockstep for Donald Trump:

The post I’d scheduled to write last week — a piece of advice for writers — is fading into oblivion along with my colleague’s Twitter post that prompted it. Instead, I took out my copy of Arlie Russell Hochschild’s Strangers in Their Own Land that I bought at the Finalists’ reading for last November’s National Book Awards. The book follows a group of white residents of southern Louisiana who had joined the Tea Party even though the core of Tea Party beliefs — ending environmental regulations, redistributing wealth from the poor and middle class to the wealthiest 1%, and weakening the safety net for people who had experienced bad luck or made a bad choice (like getting pregnant in high school) — only made their lives harder. Hochschild writes about the “deep story” that has become the core of their lives and culture, the story that fuels their emotions as effective stories do and in turn drives their political behavior. And here is the dominant story, the one she heard over and over from these Tea Party members in Louisiana who would soon vote in lockstep for Donald Trump:

You are patiently standing in a long line leading up a hill, as in a pilgrimage. You are situated in the middle of this line, along with others who are also white, older, Christian, and predominantly male, some with college degrees, some not.

Just over the brow of the hill is the American Dream, the goal of everyone waiting in line. Many in the back of the line are people of color — poor, young and old, mainly without college degrees. It’s scary to look back; there are so many behind you, and in principle you wish them well. Still, you’ve waited a long time, worked hard, and the line is barely moving. You deserve to move forward a little faster. You’re patient, but weary. You focus ahead, especially on those at the very top of the hill….

Look! You see people cutting in line ahead of you! You’re following the rules. They aren’t. As they cut in, it feels like you are being moved back. How can they just do that? Who are they? Some are black. Through affirmative action plans, pushed by the federal government, they are being given preference… Women, immigrants, refugees, public sector workers — where will it end? Your money is running through a liberal sympathy sieve you don’t control or agree with. These are opportunities you’d have loved to have had in your day — and either you should have had them when you were young or the young shouldn’t be getting them now. It’s not fair. (pp. 136-137)

Like ordinary people, dictators and would-be dictators tell stories. They tell stories about their country’s history and people to justify their absolute rule, their limitations on liberty, their official state violence against those who do not cooperate. Living in and writing about dictatorships around the world has taught me many of these stories. Here are some of them in places which I have observed and studied.

The people are naughty children who must be severely disciplined, lest they act up and create chaos.

The infantilizing of a population — a dictator’s treatment of his nation’s adults as naughty children — was the first story I came to understand when I befriended Chilean exiles living in the United States and France and later traveled to Chile to research Gringolandia and Surviving Santiago. In the process of destabilizing the elected government of Chile’s Socialist president Salvador Allende, the U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger set the tone for this story with his statement:

I don’t see why we need to stand by and watch a country go communist due to the irresponsibility of its people.

After the U.S. sponsored the military coup in 1973 that brought him to power, General Augusto Pinochet quickly imposed discipline on his wayward “children,” murdering or disappearing 3,000, and imprisoning and torturing more that 30,000 others. Torture became a primary means of cowing would-be troublemakers as thousands of broken men and women were dropped back into the community haunted by the brutality, unable to work or function within their families.

At the same time, the regime and its state-owned and heavily censored private media turned to silly entertainments to pacify and distract the population. Imported popular culture (mostly from the U.S.), variety shows, and game shows promising instant wealth to ordinary people were designed to turn everyone — including mature, educated adults — into fangirls and -boys swooning over the latest stars. The regime censored everything from intellectually and politically challenging books to letters sent between people living in the country and their relatives in exile. People warned relatives not to cross the line in tones reminiscent of elementary schoolchildren afraid that they will all be kept in for recess if one classmate acts up.

At the same time, the regime and its state-owned and heavily censored private media turned to silly entertainments to pacify and distract the population. Imported popular culture (mostly from the U.S.), variety shows, and game shows promising instant wealth to ordinary people were designed to turn everyone — including mature, educated adults — into fangirls and -boys swooning over the latest stars. The regime censored everything from intellectually and politically challenging books to letters sent between people living in the country and their relatives in exile. People warned relatives not to cross the line in tones reminiscent of elementary schoolchildren afraid that they will all be kept in for recess if one classmate acts up.

The people are beasts in the field, born to work, reproduce, and do whatever they’re told. Education is not only useless but potentially dangerous and counterproductive because they will come to see themselves as something they are not and run away or attack.

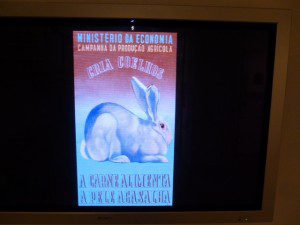

A fascist-era propaganda poster urging rural Portuguese to breed rabbits, with a subliminal message.

In a way, this is more insidious than seeing people as young children, because a despot who tells this story sees the majority of his population as not even human. It is the worldview of an agrarian society, one like Portugal during the Middle Ages, the centuries of monarchy, and the decades of the Estado Novo dictatorship of Salazar and Caetano. It is also the story that drove the country’s political and economic leaders to play an essential role in the African slave trade as the captors, transporters, and importers of human beings sold as chattel. (Yes, I love Portugal but I am aware of its complex and troubled history as well as my own country’s Original Sin.)

Neither Portuguese peasants nor enslaved African Americans were taught to read and write; in fact, it was against the law in the American South to teach an enslaved person to read. In the early years of the Portuguese dictatorship, schooling was not mandatory and many rural areas had no schools. When Salazar sought greater integration in the European community, his government established tightly regulated public schools, but only up to the sixth grade and children of the lower classes were assigned to vocational programs regardless of their intellectual ability, which the government considered useless or even dangerous. Keep in mind that Portuguese peasants were white. This story, used against one people, would eventually be used against others.

The people are milk cows, valued only for what they can give the wealthy “winners,” who have proven themselves worthy by means of their wealth. Once the people can no longer give milk — work or pay for goods and services — they are useless and deserve no support.

The Fountainhead is a commonly-taught book in U.S. high schools, especially in the kinds of suburbs where I used to live.

This corollary to the “beasts in the field” story sees money as the measure of human value, and productive activity is filtered through money. Ayn Rand and her Objectivist acolytes are the purest representations of this story. While Rand was opposed to a powerful central government, she and her followers saw no problem with successful individuals ruling like despots. Ironically, Rand herself utilized Social Security and Medicare when she became ill and unable to work.

The people are components of a well-oiled machine, each one contributing his or her abilities and taking according to his or her needs. The leadership is a vanguard that knows best where everyone fits in and is responsible for long-term planning of the economy and society as a whole.

The ideology of “scientific socialism” or orthodox Communism is familiar to most people in the United States, as the antithesis of both liberal democracy and dictatorships built on the capitalistic worldview of the previous three stories. One can see the inhuman scale of this ideology in the giant housing towers built on the rubble of bulldozed communities, cities where the entire population — homes, shops, parks, churches — was moved to allow the mining of coal discovered beneath, and walls and electrified fences constructed to keep well-honed (i.e. well-educated, as people were well-educated but had little choice in their courses of study) parts of the “machine” from rolling away.

The machine did not allow room for faith or emotion or difference. Religion was a dangerous myth, the “opiate of the masses” according to Karl Marx and a “necrophilia,” a worship of death, to the 20th century Communist leaders. Brutal and efficient police organizations like the KGB in the Soviet Union and the Stasi in East Germany rooted out dissidents and nonconformists, democrats and capitalists, people of faith and Roma people, as misfits of all kinds were seen as sand in the gears of the machine.

The people are weapons in the service of the State. There is a master race, civilized above all others, ordained to rule over or cleanse the Nation of the inferior, subhuman races.

This is the story of Nazi Germany. But Nazi Germany is far from the only country in modern history to use its “chosen” population as weapons against others. After the Civil War, the Southern aristocracy weaponized poor white people — many of whom had also been dispossessed of their lands and now worked as sharecroppers — to impose Jim Crow laws through violence against African Americans. A series of race riots and massacres — Wilmington, North Carolina, in 1898; Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1921; Rosewood, Florida, in 1923; being just a few examples — stripped thousands of prosperous Black families of their homes and businesses.

One can say that democracies can be as guilty of weaponizing its people as dictatorships. But we’re not talking about healthy democracies here. The Great Depression combined with crippling reparations payments from the First World War to bring Weimar Germany to the brink of economic ruin when a minority of voters allowed Adolf Hitler to form a government in 1933 and take absolute power within the year. The Nationalist government of South Africa, which created an apartheid system modeled on Jim Crow, rose to power in a country in which the majority of Blacks were already not allowed to vote. (In subsequent years, the Nationalist regime would also strip Indians and mixed-race Coloureds of the franchise.)

There are other stories, other models, of inhumane regimes, and some are hybrids of two or more stories. The point is, stories are powerful. And a powerful story is no guarantee of empathy, understanding, and peace. Stories can manipulate people into wars, into unspeakable acts of cruelty, into genocide. They can make listeners see the “other” as an animal, a machine, or vermin — in other words, as less than human. One of the things these five stories have in common is that they see “the people” as a monolith, stripped of human emotions and relationships. They are not character-driven, but plot-driven, forcing complex and diverse individuals into a scheme specifically designed to move them from Point A to a frightening Point B.

Excellent post, Lyn! So many sad truths.